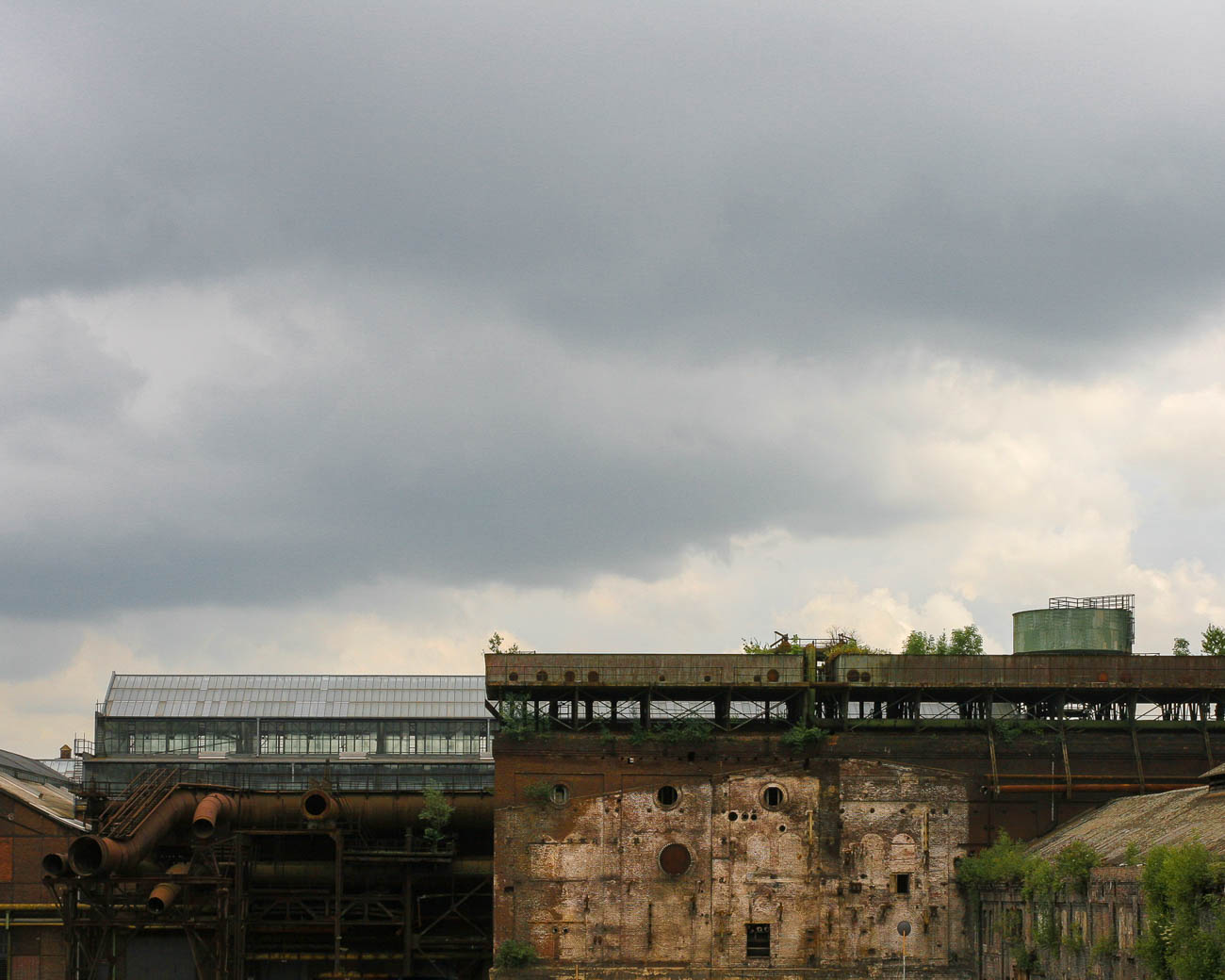

Industrial heritage

Abandoned industrial buildings and sites are footprints of our society. They bear the potential to influence the future, because they remind us on mistakes made in the past.

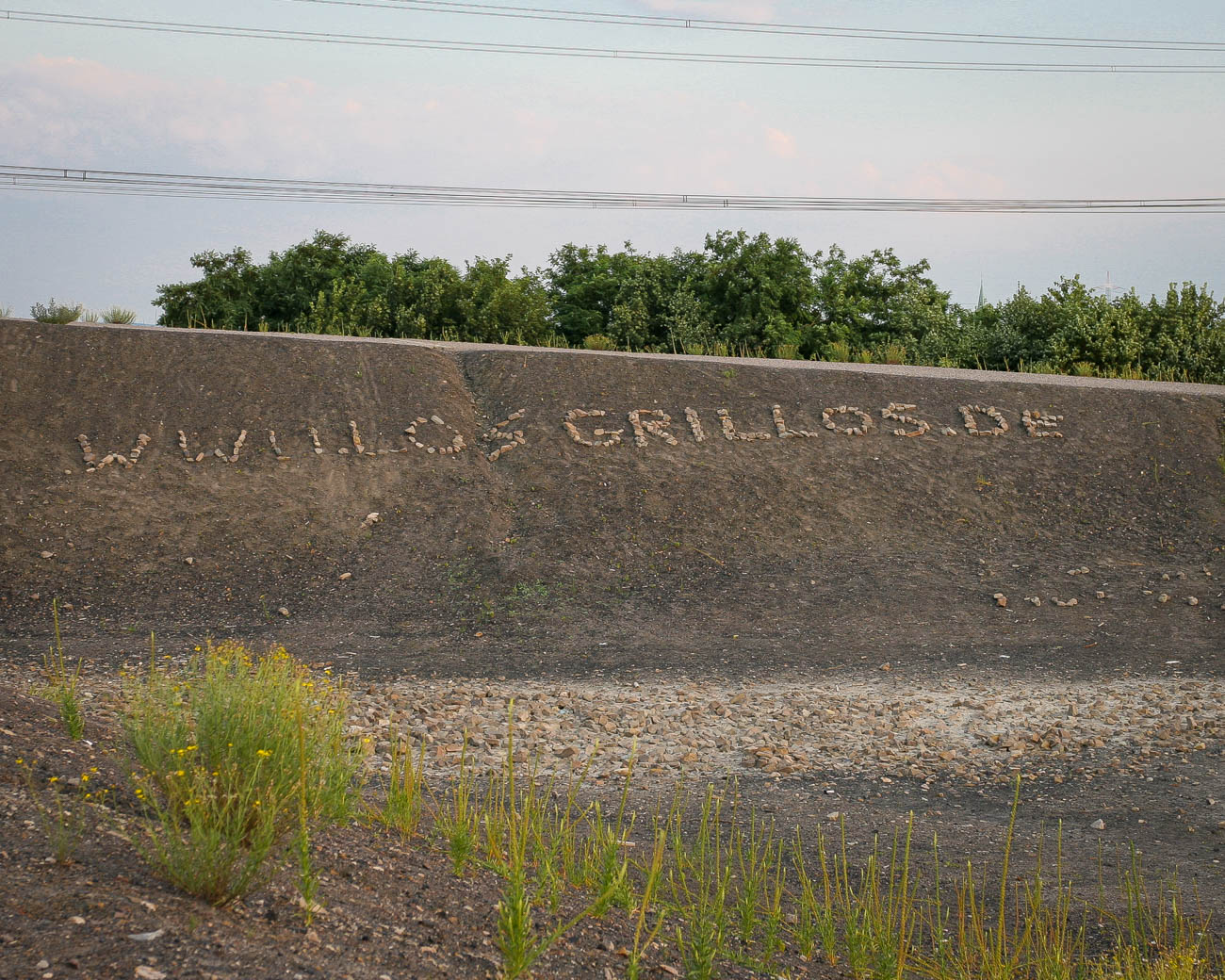

Since the very beginning of my photography journey, I have been drawn to abandoned industrial locations. Initially, I used my father’s Pentax MV 35mm Film SLR Camera, and later, my own digital equipment to capture images at various sites. On one occasion, a fellow student and I even scaled fences after dark and got finally caught by security guards. This incident felt like a scene from a James Bond movie, as we were compelled to remove the film rolls from the camera and destroy the photographs. Not surprisingly, industrial photography became my first project.

I was born and raised in the Ruhr area in Germany, often referred to as the Ruhrgebiet or Ruhrpott. This region, located in western Germany, has a rich industrial history dating back to the 19th century. It became the heart of Germany’s coal and steel production, driving the country’s industrial revolution. The discovery of extensive coal deposits led to the rapid development of mining and steel industries, transforming the Ruhr into one of the world’s most important industrial hubs. Cities such as Essen, Dortmund, and Duisburg have grown around these industries, with massive factories and mines dominating the landscape. The Ruhr’s industrial prowess played a crucial role in both World Wars by supplying essential materials for war efforts.

For many years, the Ruhr region provided employment opportunities and the prospect of prosperity, drawing individuals to work in its mines and steel factories. Initially, people came from eastern regions such as Masuria and Pomerania. Following World War II, the influx expanded to include individuals from across Europe, including countries like Italy, Spain, Greece, and Turkiye. This migration resulted in a diverse blend of cultures. Growing up in this multicultural setting, it was commonplace to have friends from various ethnic backgrounds and to value the diverse culinary traditions. Without a doubt, this situation played a significant role in shaping my personality and perspective on life.

However, I also witnessed the decline of coal and steel industries in the late 20th century that caused anxiety and fear of the future among the society, which accompanied me throughout my school and university time. Like in many other families in the region, my family was closely linked to black coal mining. One of my grandfathers was a miner and active member in the trade union. For this reason, the decline of the industry was a frequent topic in our family gatherings. Prior to relocating to Spain, I had the opportunity to visit the operational Prosper-Haniel coal mine in Bottrop. The experience was truly mind-blowing. Descending in the elevator, feeling the intense heat, navigating the narrow coal seam, and witnessing the machine scraping coal just meters away were all unforgettable moments. These experiences significantly increased my respect for miners, as they vividly illustrated the perilous nature of their work, conducted hundreds of meters below ground.

However, our coal and steel heritage extends much beyond than just the world of work. It rather shaped our entire society and lifestyle in the region. Influenced by their tough underground working conditions, my people developed a sometimes rough sense of humor and a straightforward approach to problem-solving that often unsettles other people. However, we are known for our dependability. Our strong sense of camaraderie ensures mutual support among “Kumpel” (buddies). While disagreements and debates occur, we possess the unique ability to move past conflicts and return to normalcy after a short time. When I inquired how my grandfather and his colleagues managed to work together following a dispute, he explained that the mine’s hazardous environment necessitated setting aside personal grievances, including past conflicts or prejudices. The priority was to protect your coworker’s safety, expecting the same in return.

From the late 1980s onward, it became increasingly clear that the area required a fundamental transformation to drive significant economic and industrial changes. This necessary shift occurred too late, leading to a substantial decline across the entire region. As a result, unemployment rates soared, and the area experienced a swift deterioration. In December 2018, Prosper-Haniel, the last operative coal mine was eventually closed. A hallmark event that struck me to the bones. Of course, it was foreseeable and a long process, but I never really believed that coal mining would be completely shut down in the region.

Today, the Ruhr area is celebrated for its industrial heritage, with many former industrial sites repurposed into museums, cultural centers, and parks, showcasing the region’s remarkable transformation from an industrial powerhouse to a vibrant cultural landscape. However, as in all other museums, these places of industrial culture will soon only show relics of a long-gone past.

What about the cultural identity of the region, special habits and particular character traits of my people? Well, time will show. We should expect that many characteristics deeply rooted in our coal and steel industrial background will gradually disappear, giving way to a new society with distinct attributes. Whether this transformation will be an improvement remains uncertain. However, it will undoubtedly be different and potentially more aligned with the needs of the future era.

A former mentor once shared with me a valuable insight: It’s misguided to claim that everything was either superior or inferior in the past. Such blanket statements are inappropriate. Instead, we must recognize that the world is in a constant state of flux, and our perception shapes our reality.